Native American Capital on the Banks of the Elizabeth River by Amy Waters Yarsinske

Originally published Friday May 11, 2007 in the Destination Ghent section of The Virginian Pilot, ‘Native American Capital on the Banks of the Elizabeth River’ is an article written by Amy Waters Yarsinske. The Hampton Roads area history goes back many hundreds of years, much more that most of the United States. Many of the areas in Hampton Roads have names that originate from Native American settlements and tribes.

With the commemoration of the first settlement of Jamestown 400 years ago, it would seem wholly appropriate to go back in time before the English settled the banks of the Elizabeth River. Skicoak, the most important of the Chesepiooc’s towns and mentioned in the accounts of Captains Arthur Barlowe and Ralph Lane, was later described by late nineteenth- and early to mid-twentieth-century historians to be the site chosen for Norfolk Town, on the north side of the Elizabeth River where its Eastern and Southern Branches flow together. Later, however, some twentieth-century historians and archaeologists adjusted the location of Skicoak farther down the Elizabeth River, perhaps in a location between Fort Norfolk and Lambert’s Point toward Hampton Roads, a theory supported by an intriguing article in The Virginian-Pilot dated April 13, 1905, and titled “Hundreds of skeletons dug up” with the subtitle “Mound of Indian graves excavated at Sewell’s Point and remains of red men exposed to view.”

Archeological Discoveries

While improving the grounds of the Pine Beach Hotel at Seawell’s Point (the original spelling), workmen discovered an Indian burial mound reportedly containing hundreds of well-preserved skeletons. Further investigation showed that the bodies had been buried two or three deep in a wide circle and that arrowheads and other Indian artifacts were scattered among the bones. But the initial discovery was only the beginning. The man charged with the Pine Beach Hotel beautification project estimated that thousands of other, similar burials remained uncovered. Nothing was done, however, to follow up on what the workers found. This burial place, and conceivably the site of Skicoak, were obliterated either by the western part of the Norfolk Naval Station or by private development.

Get your copy of The Elizabeth River by Amy Waters Yarsinske at Amazon today!

It is on Captain John Smith’s map of 1612 that the name Skicoak appears for the last time, demarcated by a “king’s house” on the site he called Chesepiooc, on or near the site of the burial mound discovered in 1905. After the Chesapeake were reportedly massacred between 1590 and 1607, Powhatan populated what is now Norfolk with warriors of his own whom he trusted, although they continued to be known as Chesapeake. In more recent times it has been suggested that Skicoak was located at the juncture of Indian River and the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River; this site would place Skicoak in the modern city of Chesapeake, as would another study, which suggests that Skicoak was on the Southern Branch of the river, generally near present-day Great Bridge. Skicoak’s location, or that of any significant Chesapeake tribal settlement, is best understood by models of Indian behavior forwarded by noted anthropology scholars studying the Algonquian along the Great Coastal Plain.

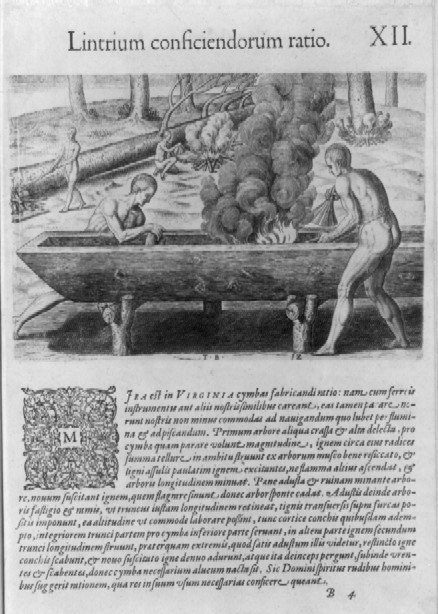

Helen C. Rountree has suggested that boats of fifty feet, such as those constructed by Indians from large trees, could not be kept on open bodies of water, as they would be subject to damage from storms and floods, nor would such vessels be left in the water permanently, only to become waterlogged. Such conditions would dictate that a harbor safe from high tides, storms and flooding was preferable; a body of water such as a small creek that afforded protection for large boats or “canowes” would have been an important consideration. Another part of the profile could conceivably be two Indian villages located on both sides of a river at the point where the river narrows. Such locations make natural land trails and over time were possibly incorporated as trading centers.

Early Exploration of the American Coast

Roanoke colonists purportedly visited Skicoak in the winter of 1586, according to David Beers Quinn’s 1955 work on the Roanoke expeditions. In Arthur Barlowe’s September 1584 account of the first exploration of the American coast, he wrote of extensive contact with Granganimo, brother of King Wingina, in the country of Wingandacoa, which the English later named “Virginia.” King Wingina was observed to be greatly obeyed and his brothers and children reverenced. Visitation and trade between Wingina’s people and Captains Philip Amadas’s and Arthur Barlowe’s parties was frequent.

During one such visit, after the Indians had been several times aboard his ships, Barlowe noted that he and seven of his party went twenty miles “into the river that runneth toward the city of Skicoak, which river they called Occam, and the evening following we came to an island which they call Roanoke, distant from the harbour by which we entered seven leagues.” Beyond the island of Roanoke there was the mainland, “and over against this island falleth into this spacious water the great river called Occam by the inhabitants, on which standeth a town called Pemeoke, and six days’ journey further upon the same is situate their greatest city called Skicoak, which this people affirm to be very great. But the savages were never at it; only they speak of it by the report of their fathers and other men, whom they have heard affirm it to be above one day’s journey about.”

Read more about the ancient Hampton Roads area in The Elizabeth River by Amy Waters Yarsinske.